UNMC, Nebraska Medicine economic impact tops $5.9 billion

This article was originally written by Bill O’Neill at UNMC “One reason that the medical center continues to have such a beneficial economic impact on

This article was originally written by Bill O’Neill at UNMC “One reason that the medical center continues to have such a beneficial economic impact on

Story from the University of Nebraska at Kearney “It’s one of the most transformational projects we’ve had on this campus ever.” – UNK Chancellor

May 6th through the 12th is the yearly celebration of nurses during Nurse’s Week. The past year has been an extremely trying time for nurses

How UNMC and Nebraska Medicine became the nation’s first responders in the fight against COVID-19.

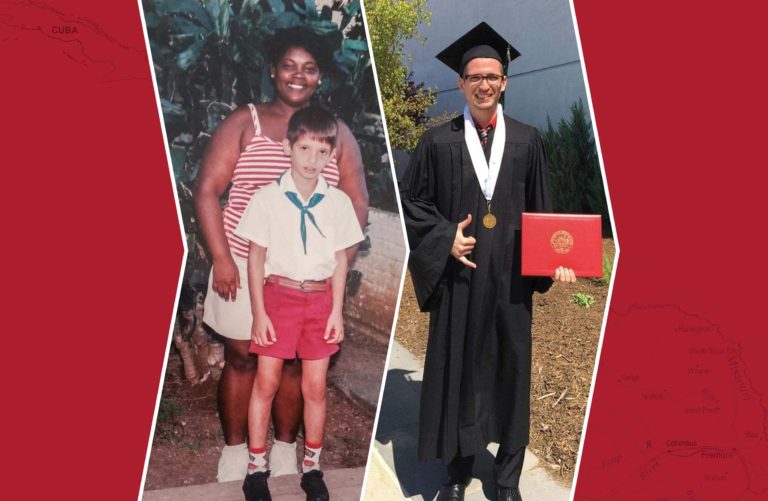

Radiel Cardentey-Uranga graduated from UNMC in May with high distinction. From Cuba to Columbus UNMC graduate overcomes obstacles to embrace opportunities. His mom made him

Group’s total contribution now exceeds $215,000 since 2014.